do women hate men now

You can’t escape it. Sabrina Carpenter’s “Man Child” is everywhere, calling guys out for never having “heard of self-care” and acting like “half of brain just ain’t there.” Olivia Dean’s “Man I Need” hits different, a subtle drag about passive guys who can’t step up: “talk to me, be the man I need...tell me you got something to give.”

And then there’s Bill Ackman—yes, the billionaire hedge fund manager—giving dating advice to young men on X, suggesting they approach women by asking “may I meet you?” The internet roasted him instantly, but the fact that he felt compelled to say anything at all? That tells you something’s seriously wrong.

Here’s the question nobody wants to ask: Do women hate men now?

The answer is more complicated than you think. Young men are struggling, and it’s creating a rift between men and women that goes way deeper than bad Hinge profiles or ghosting culture. This isn’t just about dating apps or communication styles. It’s about economics, education, and a massive shift in who has what in our society. And it’s affecting everyone, whether you realize it or not.

Let’s look at the numbers, because they don’t lie. Men now make up just 44% of college students under 25, down from 47% in 2011. In 2021, men received only 42% of bachelor’s degrees, the exact same percentage women earned back in 1970. Think about that flip. Women are 11 percentage points more likely to graduate from a four-year college in four years, and 7 percentage points more likely to graduate within six years. Among recent high school graduates aged 16 to 24, only 55.4% of men were enrolled in college in 2024, compared to 69.5% of women.

The truth is that college education isn’t just a piece of paper anymore, it’s the gateway to economic stability. The U.S. economy has shifted dramatically. Fifty years ago, a guy could graduate high school, get a solid job in manufacturing or construction, buy a house, and support a family. Those jobs haven’t disappeared entirely, but many have moved overseas or been automated. Today, 70-80% of our economy is service-based—tech, consulting, finance, healthcare—and these industries strongly favor college-educated workers.

Without a degree, men are earning 22% less than their counterparts did in 1973, adjusted for inflation. Meanwhile, college-educated women’s economic prospects have exploded. In 22 major U.S. metropolitan areas—including New York and Washington D.C.—women under 30 now earn the same or more than men their age. Nationally, women under 30 earn about 93 cents for every dollar men make, up from 88% in 2000. More women own homes than single men now. The majority of college graduates are women. The majority of people entering high-paying professional fields? Also women.

Now here’s where it gets messy. Despite all these gains, despite being more educated and earning more than ever before, 63% of recently married young women in 2023 still married men who earn more than them. Only 32% married men who earn less, and 5% had equal incomes.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t about judging anyone’s preferences. This is rooted in something deeper—evolutionary biology, social conditioning, centuries of gender norms, take your pick. The point is, research shows that the tendency for women to marry men with higher incomes has persisted even as women’s educational and economic prospects have improved. Women also generally prefer partners with similar or higher educational levels.

So do the math and run the numbers. You have a growing majority of women who are college-educated and earning good money. You have a smaller pool of college-educated men earning even more. And you have a growing number of men who are neither college-educated nor earning competitive incomes. The result? A large supply of college-educated women competing for a small pool of high-earning men, while many men without degrees struggle to be seen as viable partners.

This isn’t to say people don’t marry outside these patterns—college-educated women increasingly “marry down” in education, with about 50% marrying college-educated men, 25% remaining single, and 25% marrying men without college degrees. But when they do marry down educationally, they still tend to marry men with strong economic prospects.

So when people say young men need more confidence, they’re missing the point. Confidence comes from somewhere. It comes from feeling like you have something to offer, like you’re building toward something, like you have a future. But if you’re a young man who didn’t go to college—maybe it wasn’t for you, maybe you couldn’t afford it, maybe you just weren’t ready at 18—you’re now facing an economy that’s left you behind. You’re watching women your age buy houses while you’re stuck in your parents’ basement. You’re seeing job postings that all want degrees you don’t have. You’re swiping on dating apps where women explicitly list income and education requirements. The confidence gap isn’t personal. It’s structural.

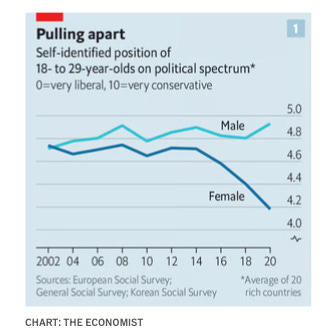

And politically? This economic divide is creating a social one. Women, increasingly liberal and independent, are pushing for reproductive freedom, childcare support, and workplace equality. Men without college degrees, a growing majority, tend to be more conservative, partly because less-educated populations generally lean that way. The values gap between potential partners is widening alongside the economic one.

So what do we do with all this? First, let’s acknowledge how far women’s rights have come. The fact that women can be financially independent, pursue any career, and not need to marry for economic security? That’s progress worth celebrating. But we also need to talk honestly about the other side. Young men are struggling, and when a large portion of young men feel left behind by society, that affects everyone. It shows up in mental health crises, in political polarization, in dating markets that feel increasingly impossible to navigate for everyone involved.

The answer isn’t for women to lower their standards or for men to just “try harder.” The answer is systemic. We need to rethink how we prepare young men for a service economy. We need better mental health resources. We need to expand what “success” looks like beyond a four-year degree. We need to challenge the social norms that tie men’s worth solely to their earning potential, and the norms that tell women they should only partner “up.”

Maybe it’s cheesy, but there’s something to learn from Pride and Prejudice. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy came from different worlds—he was wealthy and privileged, she was smart but had no fortune or status that made her an “appropriate” match. The magic of their story isn’t that one of them changed their circumstances. It’s that they both let go of the prejudices and pride that kept them apart. Darcy had to recognize how his privilege and arrogance had blinded him. Elizabeth had to see past her preconceptions.

Darcy’s confession to Lizzy gets at something real: “I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle...You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you, I was properly humbled.” Real connection requires humility from everyone. It requires seeing past the social scripts we’ve inherited about who’s “supposed” to be with whom, what makes someone worthy, what partnership should look like.

Dating feels impossible right now because the economic ground has shifted beneath our feet, but our expectations haven’t fully caught up. But more women are building lasting partnerships with men from different educational backgrounds and they’re thriving. By choosing compassion over judgment and letting go old expectations, they create space for transformation.

When everyone chooses to let go of pride and prejudice, the men often shed the “child” in “Man Child”—the defensiveness, the resentment, the rigid adherence to outdated conception of masculinity. What emerges instead is something better: not a provider in the traditional sense, but a confident partner with genuine presence. The man I need, you need, all of us need.

P.S. If you haven’t heard this song yet, it’s worth a listen.

“The confidence gap isn’t personal. It’s structural.” It is so key to understand this because this would then explain why, even if women can sustain themselves economically, most of the times, we are still trying to “date up.” And in understanding this gap, I think we can then better reflect on what is valuable for both parties - is it money? the emotional part? habits? kindness? What has to change systematically and within our biases? This topic is my roman empire haha. Well written Andy! And love all the evidence

Very thought provoking! Great piece Andy and not talked about enough - this piece has created a domino-effect for conversations here in Boston and over Facetime too!