Patagonia: From Performance to Performative

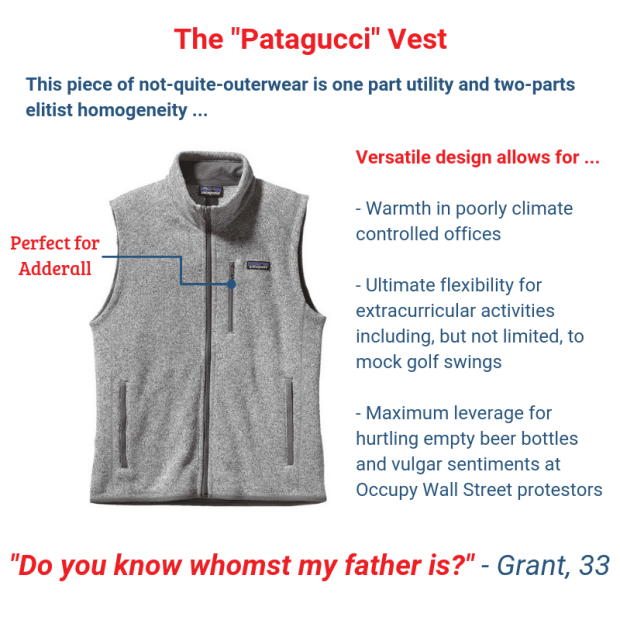

Walk into any Goldman Sachs office in winter and you’ll see the same thing: rows of Patagonia fleeces and puffer jackets. Silicon Valley? Same story. McKinsey? Check. The Patagonia vest has become the unofficial uniform of people making six figures while claiming they care about the planet.

This is the contradiction that nearly destroyed Patagonia’s brand: How do you maintain authenticity as an environmental activist company when your biggest customers are the very corporations driving climate change?

But here’s what makes Patagonia fascinating: the company actually meant it. And in 2022, they proved it in the most radical way possible.

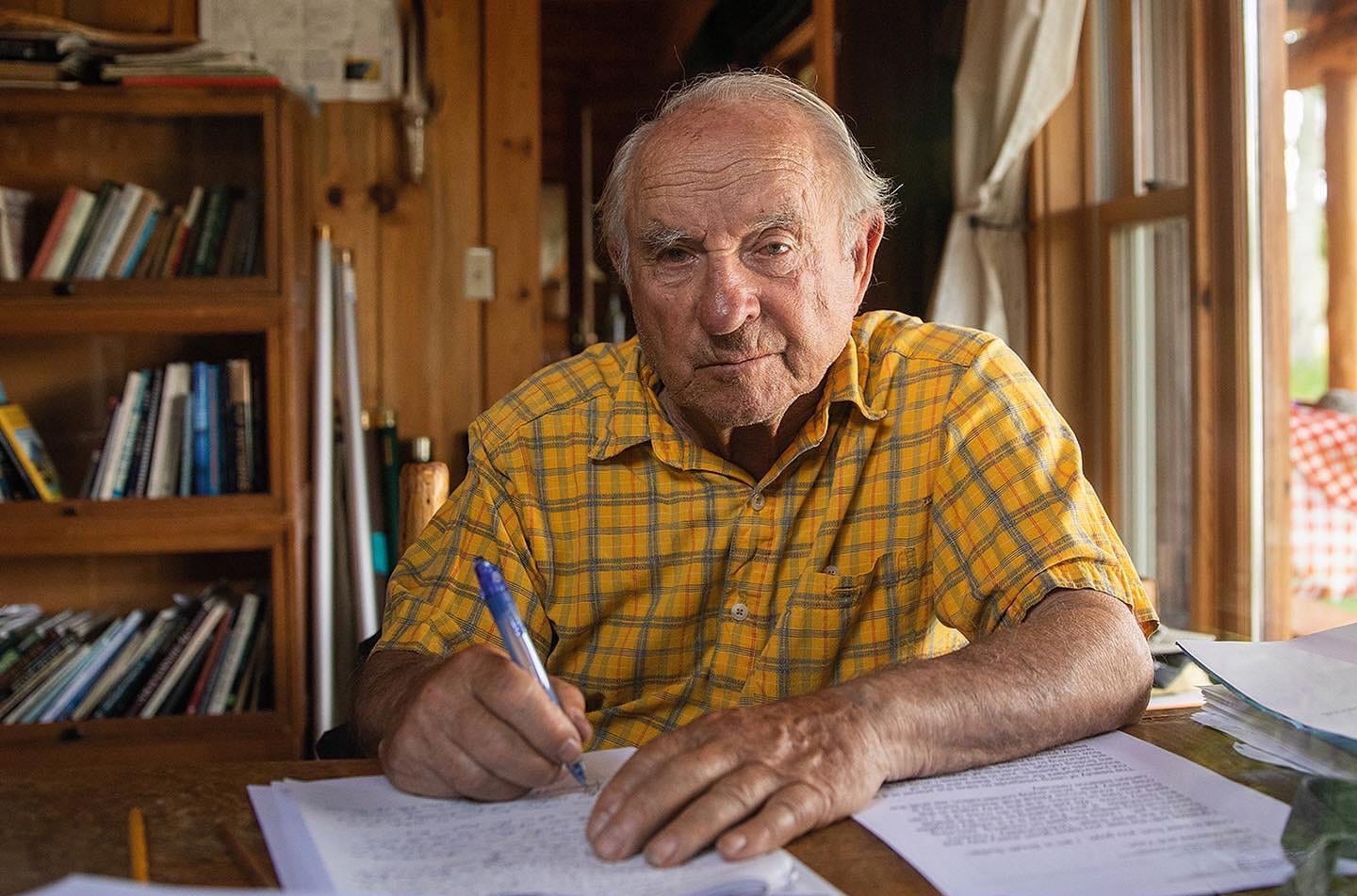

Yvon Chouinard, the 83-year-old founder worth billions, gave the entire company away. Not sold it. Not took it public. Gave it away. To fight climate change. In doing so, he created a blueprint for what authentic corporate activism actually looks like in an era where everyone claims to care but few actually do anything about it.

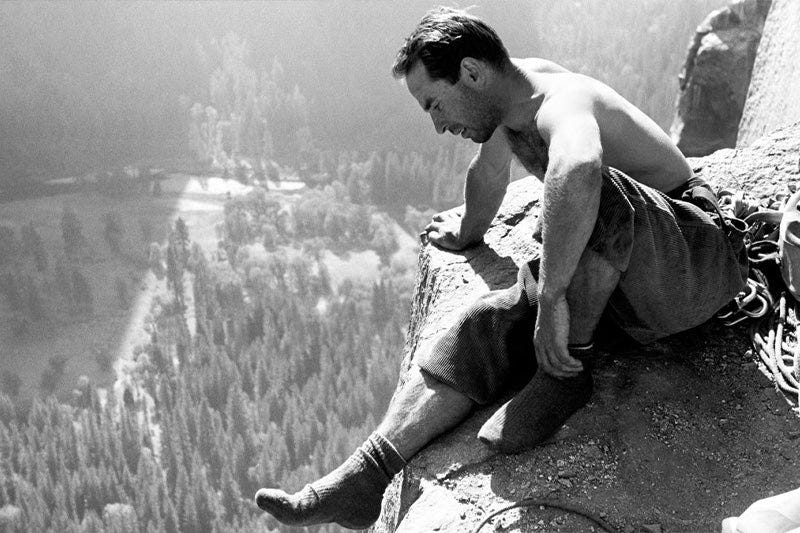

The story starts in 1957, when a 19-year-old Yvon Chouinard bought a used coal-fired forge from a junkyard because he was frustrated with climbing gear. He wasn’t trying to build a company. He wasn’t following market trends. He was a climber who needed better equipment, so he taught himself blacksmithing and started making chrome-molybdenum steel pitons—those metal spikes you hammer into rock faces. They were lighter and stronger than anything else available, and he sold them for $1.50 each from the back of his car.

By 1965, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in America. Success. Profit. Growth. Everything you’re supposed to want as an entrepreneur. Then Chouinard went climbing in Yosemite and realized his own pitons were destroying the rock faces. The scars were permanent. His product was killing the planet he loved.

So in 1972, he did something almost unthinkable in business: he stopped making the product that built his company. Instead, he introduced aluminum chocks—removable gear that didn’t damage the rock—and published an essay called “The Whole Natural Art of Climbing” that essentially told climbers to stop using his most profitable product. This launched the “Clean Climbing” movement and established something crucial about the company that would become Patagonia: it would sacrifice profit for environmental integrity. Not as marketing. As a principle.

The clothing business started by accident. Chouinard brought back a rugby shirt from Scotland in 1970 because the heavy collar prevented climbing slings from cutting into his neck. His friends wanted them. So he started importing rugby shirts, rain gear, and wool gloves—not because he wanted to be in fashion, but because climbers needed functional clothing. In 1973, he named the clothing line Patagonia, choosing a word that evoked remote wilderness and worked in multiple languages.

What followed was decades of material innovation driven not by trends but by solving real problems. In the late 1970s, Patagonia discovered synthetic pile fabric that had been discarded after the fake-fur market collapsed. They turned it into Synchilla fleece—the material that still defines outdoor gear today. In 1980, they introduced polypropylene base layers, originally used in marine ropes and diaper linings, because it didn’t absorb water. They developed the three-layer system—moisture transport, insulation, shell—that fundamentally changed how people dressed for extreme conditions.

None of this was about fashion. It was about function. And that functional authenticity is what built the brand’s reputation.

But by the 2010s, something unexpected happened. The trend of wearing high-performance outdoor gear in urban settings—dubbed “Gorpcore”—turned Patagonia into a status symbol. Those Synchilla fleeces and puffer jackets designed for Patagonian glaciers became the uniform of Wall Street and Silicon Valley. The brand that stood for environmental activism became associated with the exact people whose industries were driving climate change.

This wasn’t just awkward—it was existential. Patagonia’s entire brand identity was built on authenticity, on doing the right thing even when it hurt profits, on fighting climate change. And now their customer base included hedge fund managers funding fossil fuel expansion and tech executives building energy-intensive data centers.

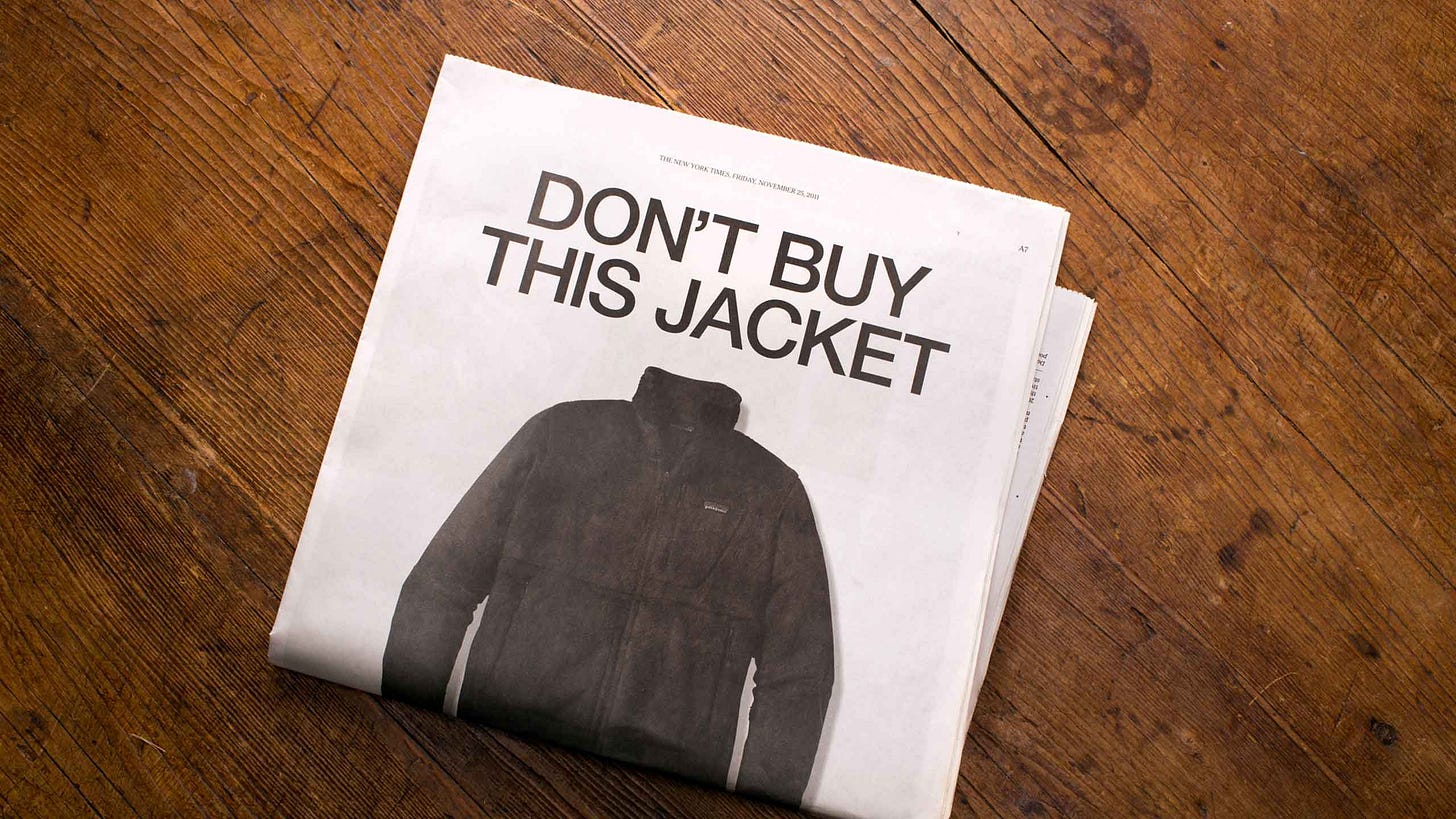

Patagonia tried to address this tension through action rather than rhetoric. They launched Worn Wear in 2017, encouraging customers to repair gear instead of buying new products. They operate the largest garment repair center in North America in Reno, Nevada, fixing over 40,000 items in 2024 alone. They created a trade-in program offering store credit for used gear. They ran ads on Black Friday saying “Don’t Buy This Jacket,” urging customers to consume less.

But the association persisted. So Patagonia took an unusual step: they ended corporate sales to certain financial and consulting firms. They turned away revenue from some of the wealthiest corporate clients in America because those clients didn’t align with their mission.

Consider what that means. A company choosing principle over profit in a way that actually costs money. That’s rare enough to be noteworthy.

But the real turning point came in September 2022, when Yvon Chouinard restructured ownership of the entire company in a way that shocked the business world. He transferred 100% of Patagonia to two entities: the Patagonia Purpose Trust, which holds all voting stock to protect the company’s mission, and the Holdfast Collective, a 501(c)(4) that holds all non-voting stock and receives 100% of profits not reinvested in the business.

What that means in practice is that every year, after Patagonia covers operating costs and reinvestment, all remaining profits—roughly $100 million annually—go to the Holdfast Collective to fight climate change. Not as charitable donations. As the company’s actual purpose. Patagonia exists to generate money for environmental activism. The clothing is the means, not the end.

Since August 2022, Holdfast has received approximately $180 million from Patagonia. That money is funding lawsuits against fossil fuel companies, supporting indigenous land protections, and lobbying for climate legislation. Patagonia sued the Trump administration over protected lands. They close stores on Election Day to encourage voting. They’ve consistently backed their stated values with legal and financial action.

This approach appears to work. By fiscal 2025, Patagonia sourced 84.4% of materials from preferred sources with reduced climate impacts. They eliminated PFAS “forever chemicals” from waterproof shells. They created the NetPlus line from recycled fishing nets. They’re not perfect—no company operating at scale can be—but the commitment is measurable and documented.

I can attest to their repair commitment personally. I own a Patagonia down jacket that survived four Toronto winters. After four years of daily wear, the entire back was worn through—fabric torn, insulation exposed. I brought it to the store expecting to be told I needed a replacement. Instead, they sent it to their repair center. A month later, it came back fully repaired. A lesser-known feature: you can request different colored patches to customize repairs. My jacket now has mismatched patches that make it distinctly mine. I haven’t encountered another brand offering anything close to that level of lifetime warranty commitment.

But this success created its own challenge. As Patagonia became synonymous with environmental consciousness, people started wearing it not because they shared those values, but because they wanted to signal that they did. The finance professionals buying Patagonia weren’t necessarily looking for gear that would last a lifetime. They were buying into an image while working for companies whose business models contradicted that image.

That’s why Patagonia’s decision to sever ties with those corporations mattered. They chose integrity over revenue. And for consumers increasingly skeptical of corporate activism, that choice carries weight.

Because the broader market context makes Patagonia’s approach unusual. Every brand now claims to care about sustainability. Every corporation has sustainability officers and ESG reports. Every CEO discusses stakeholder capitalism. But when environmental commitments conflict with profit, most companies quietly backtrack.

Patagonia hasn’t. They’ve demonstrated this repeatedly over 50 years. When their pitons damaged rocks, they stopped selling them. When fleece production had environmental costs, they switched to recycled materials. When their customer base conflicted with their values, they turned away revenue. When Yvon Chouinard could have sold for billions, he gave it away instead.

That track record is why the brand maintains credibility despite the finance vest association. The company has consistently chosen principle over profit. Not as marketing strategy. As operational practice.

The broader lesson here isn’t just about Patagonia. It’s about authenticity in corporate messaging. Consumers—particularly younger demographics—can distinguish between companies that claim values and companies that operationalize them. They notice when sustainability reports contain vague commitments without concrete timelines. They notice when companies celebrate social causes publicly while funding opposing interests. They notice when ethical claims are branding exercises rather than business practices.

Patagonia works because the commitments are verifiable. The repairs are real. The material sourcing is documented. The financial restructuring is public record. The policy advocacy is on the record. They’re not perfect—perfection isn’t possible at scale—but they’re demonstrably aligning their business model with their stated mission, even when it reduces revenue.

In a market where every brand attempts to appeal to conscious consumers through performative messaging, verifiable authenticity becomes valuable. It’s also difficult to replicate, which is why few companies achieve it.

The finance professionals almost derailed Patagonia’s brand identity. But the company’s response—severing those relationships, reinforcing their mission, restructuring ownership to ensure profits fund climate action—demonstrated that their commitment was operational, not rhetorical. That’s why, despite the mockery and the fleece vest jokes, Patagonia maintains its reputation among consumers who trust few corporate brands.

They earned it through consistent action rather than marketing campaigns. Through 50 years of choosing values over profits when those choices conflicted, even when the decision wasn’t publicly visible.

That kind of authenticity can’t be purchased through advertising. And in a market saturated with performative corporate messaging, it’s the only kind that maintains credibility.