What Makes Us Human in the Age of AI

A peek into the banks may offer us some hints

The earnings calls came and went, as they always do. In the past week, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup released their quarterly results, and the numbers told a familiar story. JPMorgan reported investment banking fees up 42%, driven once again by what Wall Street calls the “deal-making supercycle.” But buried beneath the headlines about capital markets and trading revenues was something more profound, something that struck me as I listened to executives discuss their technology investments. These institutions are not just banks anymore. They are becoming technology companies. And with that transformation comes a question that extends far beyond finance: What makes us human in the age of AI?

To understand what is happening, we need to start with what banks actually do. At its heart, banking is elegantly simple. Take deposits from people who put money in their checking and savings accounts, then lend that money out to individuals who need loans or credit cards, to families who want mortgages, and to businesses ranging from your neighborhood bagel shop to billion-dollar enterprises. Make sure you charge enough interest to cover your costs—paying interest on those deposits, paying your employees, keeping the lights on—and ensure that your clients can actually pay you back.

That last part is where things get complicated. The difficult reality of lending at scale is that clients do not always pay you back. We have seen it recently with the bankruptcies of companies like First Brands and Tricolor. But this is also where technology becomes remarkably efficient. Systems can perform Know Your Customer verification to assess a client’s risk and prevent fraud. Risk models can generate probabilistic outcomes on whether someone will repay a loan. And here is the beautiful mathematics of it all: when you run these operations on a large enough scale, using the same model, the law of large numbers works in your favor—unless, of course, your model is fundamentally flawed, in which case you are in serious trouble.

Think about it this way. Banks focused on lending are effectively becoming software companies. You write the code once, refine it, and then deploy it at scale with margins that improve as you grow. The lending itself can theoretically expand without limit, while the cost of running the model remains relatively fixed. It is a simplification, certainly, but it captures how the industry has evolved.

Companies have already proven this model. SoFi operates as an entirely digital bank with a banking charter. Chime markets itself as an all-in-one banking app with no monthly fees, no overdraft charges, and no minimum balance requirements. They are not exceptions anymore; they are the new normal.

Consider this thought experiment. It is the early 2000s, and you want to take out a personal loan for law school. You drive to your local bank branch, sit down with an advisor, fill out forms, and submit stacks of paperwork. Someone performs the underwriting manually, combing through your documents, assessing your creditworthiness. The process takes days. When everything is said and done, you are looking at a week or two before you hear back about your loan.

Now fast-forward to today. You open your laptop, fill out an online form in thirty minutes, submit it, and wait a few hours. The system processes your application, runs it through algorithms that assess thousands of data points, and returns a decision. Your credit card or loan approval arrives before dinner. The transformation is not just about convenience, though that matters. It is about efficiency, reduced risk for the bank, and dramatically lower costs. Hiring and training employees is tremendously expensive for banks. Automation changes the equation entirely.

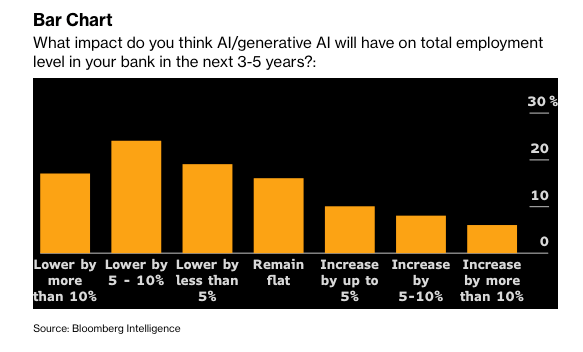

The current chapter of this story involves generative AI, and it is playing out across every division of traditional banking. Trading floors have been in structural decline for years as algorithms replace human traders. Asset and wealth management are being transformed. Investment banking and corporate banking are next. The scale of this shift is staggering.

Recently, JPMorgan Asset Management, which manages more than $7 trillion, announced it is replacing proxy advisers with its AI system called Proxy IQ. Proxy advisers are specialized firms that help institutional investors decide how to vote their shares at corporate shareholder meetings, essentially guiding trillions of dollars in voting power. The new tool will aggregate and analyze proprietary data from over 3,000 annual meetings, eliminating the need for external advisors. The bank stated this transition allows it to vote solely in clients’ best interests. It is the first major investment firm to make such a move.

This is just the tip of the iceberg.

Beneath the surface of these corporate announcements, a new generation of startups is reimagining what it means to work in finance. Consider Rogo, a company with the audition ambition of becoming what its founders call an “AI-native investment bank.” The company was co-founded by Gabriel Stengel, who worked at Lazard, and John Willett, who worked at JP Morgan and Barclays, former investment bankers who experienced firsthand the brutal hours junior analysts spend on manual research, building financial models, and crafting presentation decks.

Rogo raised $50 million in a Series B round, bringing its total funding to $75 million. The platform integrates into bankers’ daily tools, primarily Excel, and automates tasks that traditionally consumed the lives of first-year analysts. It can draft memos, build models, create slides, and conduct research, all the “grunt work” that banking analysts endure during their hundred-hour work weeks. The promise is that human bankers can focus on what supposedly distinguishes senior professionals: client relationships and strategic thinking.

What Rogo and companies like it are doing is effectively eliminating the entry-level positions at investment banks and private equity firms. The work that remains is analyzing deals to determine whether they will generate returns, and the sales work where managing directors source opportunities. Those human elements, judgment and relationships, are not being replaced anytime soon. But the traditional path of paying your dues as a junior analyst, learning through exhaustion and repetition, is vanishing.

The employment data hints at the deeper transformation underway. At Harvard’s MBA program, only 4% of students received no job offer within three months of graduation in 2021; by 2024, that figure swelled to 15%. MIT saw a similar change, with its share of offer-less graduates climbing from 4.1% to 14.9% in just three years. And while experts suggest that an AI-fueled finance job takeover is largely “smoke and mirrors” for now, the direction is clear. A report from Citigroup found that 54% of financial jobs have a high potential for automation, more than any other sector.

So if we strip away all the work that AI can do better and faster than humans, what is left for us? I believe there are two essential capacities that remain distinctly human, at least for now.

The first is critical thinking, not the buzzword version taught in corporate training sessions, but the real thing. The ability to analyze an issue from multiple angles, gather facts and evidence from imperfect sources, synthesize them into a coherent understanding, reach a conclusion, and then act on it with conviction. This is where you see diverging performance between funds and banks. It is what we call strategy and execution.

The stock market offers a fascinating case study. Right now, investors are grappling with what some call the AI bubble, and it is remarkable to watch sophisticated people with access to the same information reach completely opposite conclusions.

Some investors see warning signs everywhere. They compare the current investment cycle to 1997, right before the dot com bubble. They point to stretched multiples on the S&P 500 index. They note OpenAI’s spending commitments exceed $1 trillion despite generating only a few billion in revenue. When DeepSeek released its model, these skeptics argued that large language models do not need as much compute power as previously imagined, potentially undermining the entire thesis behind data center investments. Prominent figures like Howard Marks have suggested that while the technology itself may be transformative, the front-loading of spending will likely create a bubble.

On the other hand, many investors, myself included, believe the investment in AI is far from a bubble. We see rapid advancement in AI training, scaling of models, and increased specialization in fields like drug research and autonomous driving. The technology is expanding into images, voice, and video. We point to structural bottlenecks that actually constrain enthusiasm — limited supplies of high-bandwidth memory, the challenge of building data centers and powering them. If anything, we argue, the addressable market is larger than currently imagined, and current spending remains underwhelming relative to the opportunity.

Both sides are smart people looking at the same data. What separates them is the ability to think through complex, ambiguous situations and make structurally sound decisions. This requires extensive learning and training in a domain. As Ken Griffin stated in a recent interview, AI can make short-term decisions in high-frequency trading, decisions made in seconds, but once you extend the timeframe, the models break down.

The second distinctly human capacity is building relationships. While many people hear “sales” and think of something negative—pushy, transactional, inauthentic—what it really means in high-stakes banking is creating genuine, trusting connections. When you need to get a deal done, you call someone you trust. When you are making a billion-dollar decision, you want to work with people you have built a relationship with over years.

This ability to build trusting, genuine working relationships is more difficult for AI to disrupt. I will not claim AI cannot eventually do it. In many ways, we do not even need AI for this disruption, ratings on Google Maps and Amazon already serve as trust validators. But in high-stakes banking, transactions require deep trust, and trust still comes primarily from human connection.

All of this extended reflection circles back to the fundamental question: What makes us human? Not in some abstract philosophical sense, but practically, in a world where machines can do more and more of what we once considered uniquely human work.

The answer, I think, is this: the ability to think freely and to be fully present with our senses, to imagine possibilities that do not yet exist, to connect with one another on a level deeper than transaction and efficiency. These capacities seem obvious when stated plainly, yet they are increasingly out of reach for many of us who grew up with smartphones and TikTok, who learned to seek answers in thirty-second clips rather than sustained thought, who built digital networks but struggle to build genuine, trusting relationships.

The great irony of our moment is that we have tools that could empower our lives in unprecedented ways, yet many people are becoming enslaved to them instead. They ask AI for answers rather than developing the capacity to think through problems themselves. They optimize for efficiency rather than meaning. They mistake productivity for purpose.

The transformation of banking offers a preview of what is coming for every industry. The routine work will be automated. The work that requires pure processing power or pattern recognition will be handled by machines. What remains will be the work that requires judgment, creativity, and human connection—the work that makes us most fully human.