The End of Cheap: How the US-China Trade War Is Rewriting Gen Z's Shopping Reality

Stop scrolling for a second and check the tag on what you’re wearing right now. China? Vietnam? Bangladesh? There’s a good chance at least one item was manufactured in a country in the Pacific. And if you’ve ever impulse-bought a $12 phone case from Temu or filled a Shein cart with $3 crop tops, you’ve been living in what might be the final days of the cheap goods era.

The US-China trade war isn’t just diplomatic theater anymore. As of now, this trade war is fundamentally reshaping where products go, how much they cost, and what Gen Z can actually afford.

The numbers tell a stark story. China’s exports to the US plunged 25% in October 2025 compared to the same month the previous year, marking the seventh straight month of double-digit declines. Meanwhile, exports to ASEAN countries jumped 13% in the first half of 2025, a $37.1 billion increase. This isn’t a temporary blip. It’s a structural realignment that will define Gen Z’s economic reality for decades.

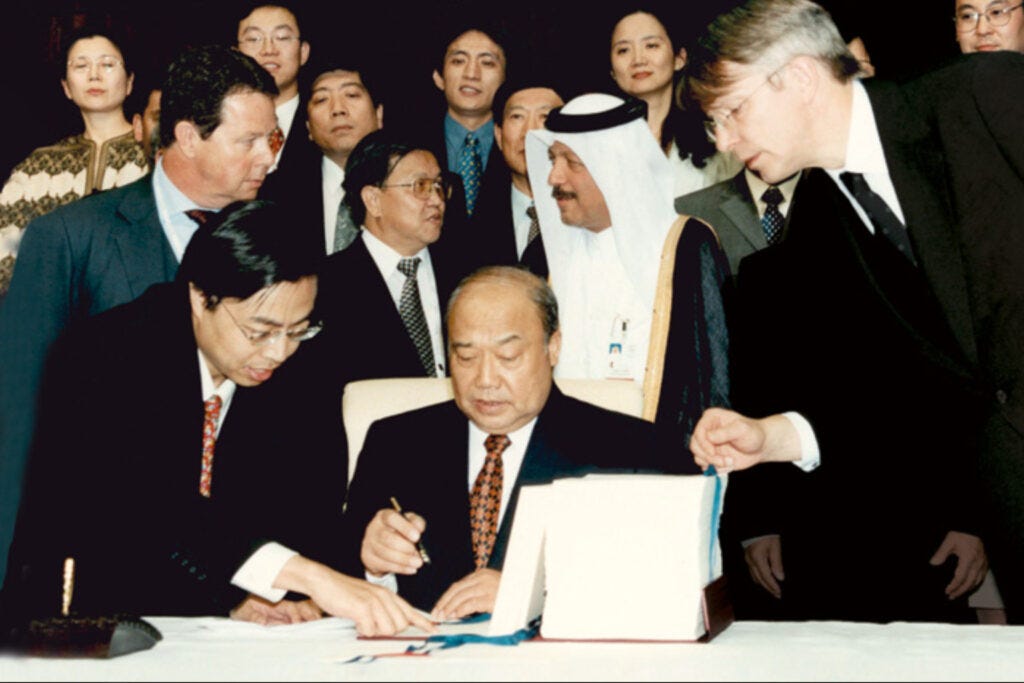

To understand what we’re losing, let’s rewind to 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). This was globalization’s peak moment, when the US gained access to hundreds of millions of workers who could produce goods at a fraction of domestic costs. Trade between the two countries exploded from $116 billion in 2001 to over $660 billion by 2024. For Gen Z, this meant growing up in a world where “cheap” was the default.

The economics were simple. American companies like Nike spent millions on R&D, branding, and marketing to sell shoes for $100, but the actual manufacturing cost—labor, materials, shipping—was closer to $30. Nike captured massive margins through brand value while Chinese factories captured very little.

Then came the disruptors like Shein, Temu, AliExpress. These platforms asked a radical question: what if we just skip the brand markup entirely and go straight to the consumers? No glossy ad campaigns, no celebrity endorsements, just direct-from-factory goods at rock-bottom prices. A $15 dress. A $3 phone case. A $30 pair of jeans. It felt like a game, and Gen Z played along enthusiastically—posting haul videos on TikTok while simultaneously advocating for environmental responsibility. The cognitive dissonance was real, but so were the deals.

Behind those suspiciously cheap prices was a policy called de minimis, a trade rule that allowed packages worth under $800 to enter the US duty-free with minimal inspection. Originally intended for tourists bringing back souvenirs, Chinese e-commerce giants weaponized it into a business model. Shipments using de minimis exploded from 140 million in 2014 to 1.36 billion in 2024. But on August 29, 2025, Trump shut it down globally. The end of de minimis could cost US consumers at least $10.9 billion, or $136 per family, according to a 2025 paper by economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research, with low-income and minority consumers feeling the biggest impact.1 The effects were immediate and brutal. Temu’s US daily active users plummeted 52% in May versus March, while Shein’s dropped 25%. Both companies raised prices, slashed advertising budgets, and scrambled to build US warehouses to avoid direct imports from China.

But Chinese goods aren’t disappearing, they’re just taking a detour. China-ASEAN trade is projected to hit $1.05 trillion in 2025, with China running a $278 billion surplus, as manufacturers reroute products through Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Cambodia, where they’re finished or relabeled before heading to Western markets. But this workaround comes with consequences for these countries. For Southeast Asia, it means deflationary pressure as the sudden influx of cheap Chinese goods threatens the competitiveness of the local economy, and hence leads to job loss.

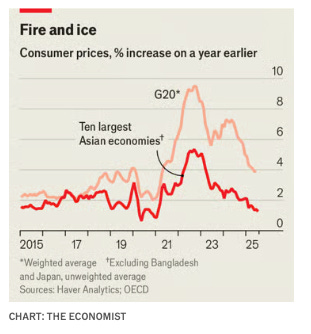

Consumer prices fell outright in China and Thailand, while inflation across Asia’s ten biggest economies averaged just 1.3%. In Thailand, where cheap Chinese models increasingly dominate, car prices fell 6% in the year to July. In Indonesia, the textile sector laid off 80,000 workers in 2024, with 280,000 more jobs at risk in 2025. For American consumers, that Southeast Asian detour often means higher prices than direct Chinese imports, but still lower than US-made alternatives. It’s a new middle ground we’re still learning to navigate.

Gen Z is getting squeezed. The era of consequence-free cheap goods is over, but the era of living wages hasn’t arrived. The inflation divergence is real—while Asia experiences deflation from Chinese goods flooding their markets, the US is seeing the opposite effect. Those $30 Shein jeans? They’re climbing toward $40-45. Even Nike sneakers made in Vietnam now face higher costs.

This hits different depending on where you fall economically. About 48% of de minimis packages were shipped to America’s poorest zip codes, while only 22% went to the richest ones. For lower-income Gen Z, cheap goods weren’t just convenient, they were an economic lifeline that made it possible to look put-together on a tight budget. Their absence doesn’t just mean paying more; it makes the wealth gap visible in what people can afford to wear and own.

The bigger picture is structural. This isn’t just about Shein prices. China now faces a steep 55% total tariff, consisting of a 25% Section 301 tariff, a 20% fentanyl-related tariff, and a 10% reciprocal tariff. We’re not getting cheap Chinese EVs anytime soon, even though they’re genuinely impressive—the $50,000 electric cars I saw in China put American automakers like GM and Ford to shame. Semiconductors, soybeans, minerals—the decoupling extends to sectors people don’t even think about until they affect phone prices or grocery bills.

The loss of cooperation extends beyond shopping. Fewer Chinese students in US universities. Less research collaboration. Tech transfers drying up. The invisible infrastructure of exchange that enabled cheap goods also enabled career opportunities, education access, and innovation. All of it is fracturing simultaneously.

What makes this moment historically unique is that Gen Z’s formative shopping years are coinciding with de-globalization. We’re the first generation in decades experiencing a shrinking global marketplace, not an expanding one. In May 2025, the US accounted for just 7.1% of China’s total exports, the lowest share recorded since 2001. When Trump first took office in 2017, America absorbed nearly 18% of China’s exports. That is a fundamental reorientation of global trade.

This isn’t meant to be doom-scrolling material though. Understanding what’s happening is the first step toward adaptation. That “normal” price you’re used to? It was artificially low, subsidized by a trade relationship that no longer exists. Prices are resetting to a new baseline. Vietnamese, Indonesian, and Thai sellers are building their own direct-to-consumer platforms that are often more expensive than peak-Temu prices but still cheaper than US retail. Apps like Shopee are gaining traction outside the US, and some savvy Gen Z shoppers are already finding workarounds. When new cheap goods become less accessible, the circular economy becomes more attractive—thrifting and secondhand markets aren’t just environmentally conscious choices anymore, they’re economic necessities.

We can’t go back to 2015, when a $15 Shein dress and next-day Amazon shipping felt like birthrights. The US and China aren’t cooperating like they used to—not on trade, not on research, not on climate, not on much of anything. That $30 jean isn’t necessarily gone, but it’s becoming a $40-50 jean, and that shift ripples through every aspect of Gen Z’s economic life. The era of cheap isn’t over, but it’s morphing into something different. We’re watching the world split into blocs in real-time, and unlike older generations who experienced globalization as expansion, we’re experiencing it as contraction. The question isn’t whether we can preserve the old system—we can’t. The question is how we navigate the new one. And for a generation already dealing with student debt, housing costs, and climate anxiety, watching affordable goods slip away feels like another door closing. But understanding why it’s happening is the first step toward figuring out what comes next.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Amit Khandelwal, et al. “The Value of De Minimis Imports.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 32607, August 2025. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32607.